Teleostability and Uncreated Energies : The Living Finality of the Universe

- Cyprien.L

- Aug 14, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Aug 23, 2025

Introduction

Modern science describes the universe as a network of interactions, governed by physical laws that seem immutable. It observes the interdependence of phenomena: every being, every particle, every system is linked to others in an invisible web. Yet this description leaves a fundamental question unanswered: why does this order persist? Why does the universe not collapse into chaos, and why has it, over billions of years, maintained an orientation that makes possible the emergence of life and consciousness ?

This is precisely the question to which the concept of teleostability responds: the property by which the universe, and everything that exists within it, remains oriented toward its ultimate end (telos) and stays ordered to it — not merely by an initial impulse, but by the continual action of God, who preserves every being in existence and sustains the harmony of the whole. This vision goes beyond teleonomy, which is only an apparent finality arising from natural mechanisms, to affirm that a personal First Cause acts at every moment.

Palamite theology, by distinguishing between the essence and the energies of God, offers an original and powerful answer to this question. It makes it possible to understand how God can be both immutable and active in the world, how He remains infinitely transcendent while truly communicating Himself to His creation. Within this framework, teleostability takes on its full meaning: it is the cosmic effect of the active presence of God in the world.

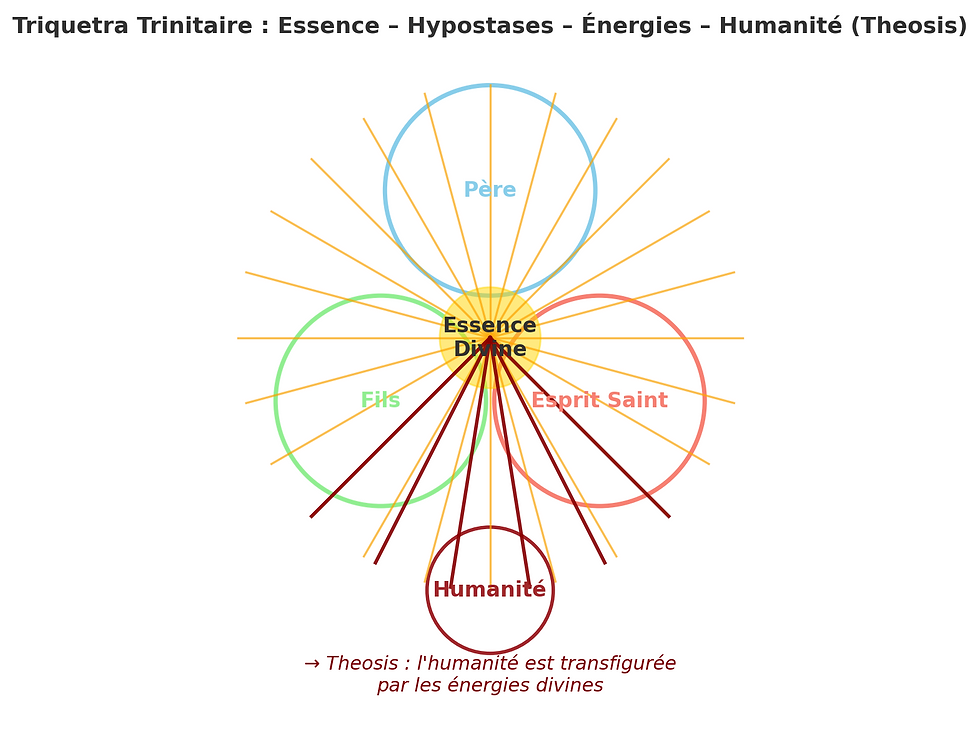

I. Foundations: Essence, Energies, Hypostasis, and Person

To understand teleostability in the light of Palamite theology, we must first grasp three fundamental notions: essence, energies, and hypostasis.

Essence (ousia) — what God is in Himself, in His innermost being. The divine essence is absolutely inaccessible to creation; neither human intelligence nor even the angels can comprehend it. This is the domain of absolute apophaticism: we cannot say what God is in His essence, only what He is not.

Uncreated Energies (energeiai) — the divine operations by which God manifests Himself and acts in the world. They are not created realities but God Himself in action, distinct from His essence without being foreign to it. It is through these energies that life, light, movement, and finality are imparted to the universe.

Hypostasis — the concrete mode of existence of a nature. In the case of the divine persons, each hypostasis is a unique subject who fully possesses the divine nature. For spiritual creatures (human beings, angels), the hypostasis is the personal subject who bears the created nature.

The Atomic Metaphor and the Hypostatic God

If we accept the Trinitarian conception of God, then the classical Thomistic scholastic position can appear — at least to my eyes — as a step aside, a hesitation, almost a refusal to carry through the radical implications of the Trinity. The scholastic desire to preserve unity risks introducing a kind of superiority of essence over person, as if essence were the ultimate metaphysical substrate while the hypostases remain secondary “manifestations.” In so doing, scholasticism, for all its rigor, runs the risk of producing precisely what it sought to avoid: a conceptual God, the “God of the philosophers,” an abstract essence without living communion.

By contrast, the intuition of the Eastern Fathers and their heirs was profoundly different. Rooted in mystical experience rather than in conceptual univocity, they perceived something organic in God — an existence at once simple and relational, marked not by division but by living communion. In their apophatic and experiential sensibility, they could affirm without hesitation that the essence of God has as its hypostasis the Persons of the Trinity. Essence never exists “by itself” as a bare abstraction; it always subsists in the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

The atomic metaphor may help us glimpse this truth in contemporary language. The nucleus represents the essence: indivisible, inaccessible in itself. Yet the atom is not a bare nucleus; it exists only as borne by its particles — protons, neutrons, electrons. Remove the particles, and what you have left is no longer an atom in reality, but only an abstracted idea. In the same way, remove the hypostases, and what you are left with is no longer the living God but a concept, a principle. It is only in the Persons — Father, Son, Spirit — that the divine essence truly subsists and radiates.

This is not a conceptual contrivance, but something remarkably simple and organic, reflected in creation itself. The human being, made in the image of God, exists not as an abstract “nature” but always as a concrete person. The atom, which composes every body, exists not as a disembodied nucleus but through the interplay of particles and fields. If God declared His creation “good” and “beautiful,” then He is truly an artist — and is it not the signature of every artist to leave his trace, his image, in his work? To discern in creation analogies of God’s own way of being is not a flight of fancy, but perhaps the most logical conclusion.

Thus to say that the divine essence exists without hypostasis would be to reduce God to abstraction, to depersonalize Him into the “God of the philosophers” that Pascal rejected. The Christian confession, both East and West, is more radical: the divine essence never exists alone, but always in the three hypostases. The hypostasis is not a mask placed on essence, but the real mode of its existence. Just as an atom is not only a nucleus but exists as such only with its constitutive particles, so too the divine essence exists only in the divine Persons. Remove an hypostasis, and you strip God of His living, relational reality. The Christian God is therefore not a principle, but a communion of love — a God who is Father, Son, and Spirit.

Here, the notion of person becomes central: a nature never exists except as borne by a hypostasis. For man, this means that our human nature is not an abstraction: it always exists embodied in a concrete person. Likewise, in God, the divine nature always exists in the three hypostases — Father, Son, and Holy Spirit — who live in an eternal relationship of love.

It is this personal dimension that prevents teleostability from being reduced to a mere cosmic mechanism. The universe is sustained not by an impersonal force, but by a living relationship: creation exists because God wills it to exist, at every moment, and because His energies continually communicate being to it.

II. The Interdependence of Phenomena and the Continuous Divine Support

The physical and ecological sciences today confirm that the universe is a network of interdependence. No being exists in isolation. Forests breathe thanks to the oceans; the cycles of water depend on the mountains; and the human body itself lives by means of a complex balance of organs, bacteria, and invisible flows. This fabric — which Eastern traditions sometimes call “universal interdependence” — finds in Palamite theology an even deeper reading: this web of relationships exists and is sustained only because God, through His energies, upholds it at every moment.

Teleostability expresses this reality:

God does not merely “launch” the universe, like a watchmaker who abandons his watch after winding it.

He acts continually, not to change His plan, but to maintain each being in existence and in its orientation toward the telos.

This sustaining is both universal (concerning the whole cosmos) and personal (each being receives existence as a gift addressed to it).

Here the analogy with the essence/energies distinction becomes invaluable. In scholastic theology, one speaks of conservatio in esse : God preserves things in being through continuous action. Palamite theology enriches this language by showing that this action is not a mere “injection” of being, but a living communion: the divine energies are not a neutral current, but the very life of God given to the world.

This has a direct consequence for the understanding of interdependence: it is not only a biological or cosmological fact; it is the sign of a greater reality — the shared participation of all beings in the divine life that sustains them. Even inanimate objects, even “dead” matter, subsist because God communicates being to them. Living beings, in addition, receive the capacity to participate consciously in this gift.

In this sense, teleostability differs from mere mechanical stability : it is a relational stability, rooted in the very act by which God gives Himself and sustains the world.

III. Person and Relationship: The Living Heart of Teleostability

If teleostability cannot be reduced to a cosmic mechanism, it is because it rests on a central truth: everything that exists exists only in and through a living relationship.

In God, this relationship is eternal and perfect: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit exist in a communion of absolute love. Each of the three hypostases fully possesses the divine nature, yet they are distinguished by their mutual relations: the Father begets the Son, the Son is begotten of the Father, the Spirit proceeds from the Father (and, according to Catholic theology, from the Father and the Son). This communion is the source of all reality.

Thus, the act by which God creates and sustains the world is not an impersonal gesture: it is the extension of this Trinitarian love. The uncreated energies are not an anonymous force, but the concrete expression of that relationship. In teleostability, it is therefore a Person who sustains, not an abstract force.

This has a major implication for the Christian vision of the universe:

Things are not maintained in being by necessity, but by free and loving will.

Creatures are not cogs in a closed system, but participants — to varying degrees — in this communion.

The dignity of each being stems from the fact that it is willed, sustained, and accompanied in its journey toward its finality.

This is also what profoundly distinguishes Christian theology from certain Eastern or naturalist philosophies: the universe is not an impersonal totality absorbing its parts into an endless cycle; it is a creation upheld by a personal relationship, and that relationship has a face — the face of Christ, in whom “all things hold together” (Col 1:17).

Philosophical Objections — Especially Buddhist

Some Buddhist schools, drawing on the doctrine of śūnyatā (emptiness), assert that an absolute, immutable God could not be in a real relationship with the world without changing.

He would therefore be totally separate, or else He would have to give up His immutability in order to act. The Palamite distinction bypasses this dilemma: God truly acts in the world through His uncreated energies, without His essence undergoing any change. This avoids both the vision of an isolated, inactive God and that of a God who transforms Himself by entering into history.

Apophaticism and the Knowledge of God

Apophaticism (apophasis, “to deny, to take away”) is the method of speaking about God by saying what He is not, in order to preserve the transcendence of His essence. In this perspective, we do not know what God is in His essence, but we truly know who He is through His energies: merciful, creator, savior, friend of mankind. The difference with Buddhist śūnyatā is that, for Christianity, this mystery is not an impersonal void but a personal fullness — a living God who calls to communion.

Man, created in the image and likeness of God, bears within himself a unique mark: he is capable of knowing and loving the One who sustains him. In this sense, tasting the Infinite — through contemplation, prayer, mystical experience — does not dissolve us into an abstraction, but establishes us more deeply as persons, because this Infinite is personal.

IV. From Teleostability to Metaphysical Ecology

If every being exists and is sustained by a relational act of God, then the world around us is not merely a backdrop nor a storehouse of resources to be exploited — it is a theophany, a real though veiled manifestation of the divine presence.

The uncreated energies are not poured out upon humanity alone; they flow through and uphold the entire cosmos, from the heart of a star to the smallest cell. In this light, every created reality has value in itself, apart from its immediate usefulness to man, for it participates, in its own degree, in the great orientation toward the telos.

Here emerges what can be called metaphysical ecology:

It goes beyond scientific ecology by integrating the ontological dimension: to protect nature is not merely to maintain a physical or biological balance, but to respect a reality sustained directly by God’s creative act.

It also goes beyond political ecology by affirming that respect for life flows from the recognition of its finality and its connection to the Creator.

It implies that animals, though not persons, are nonetheless individuals willed by God and sustained by His action. This grants them real dignity, which forbids any brutal instrumentalization.

In this vision, to destroy a species or pollute a river is not merely an environmental mistake — it is an act of rupture with the harmony willed and upheld by God. It is, at our own scale, the breaking of a link in teleostability.

Conversely, to protect and beautify creation is to cooperate in the divine work, to participate actively in the ordered sustaining of the universe. It is a form of cosmic liturgy, where every act of care toward the earth, the animals, or even matter itself becomes an act of alignment with the relational order willed by God.

Thus, teleostability is not reducible to an abstract metaphysical concept. It sheds light directly on how we live, produce, consume, and relate to the world. It calls for a radical respect for life, rooted not in fear of losing our comfort, but in love for the One who sustains it and leads it to its fullness.

V. Conclusion: The Harmony of the Telos

Teleostability makes it possible to reconcile several visions that too often ignore or oppose one another: the precision of Western scholasticism, the mystical intuition of Eastern Palamite theology, and the contemporary sensitivity to the interdependence of life.

By affirming that the universe remains oriented toward its ultimate end not through an initial impulse, but through the continual action of God, it reminds us that the divine Being is both immutable and active, transcendent and immanent. The essence/energies distinction shows how God can remain inaccessible in His being while truly giving Himself in His action, thus resolving the classical objection that an immutable God would be incapable of acting in time.

This vision enriches and nuances the classical scholastic conception of the actus purus — God as Pure Act, without any potentiality, whose acting is eternal and simple. Where scholasticism emphasizes the unity and eternity of the divine act, the Palamite perspective highlights that this eternal act is truly manifested in time through His uncreated energies, without implying any change in the divine essence. Thus, God does not need to “change mood” or “decide” within time to create or intervene: His good will is eternal, yet He becomes present in history as a living relationship and free openness, not by necessity but by grace.

This sustaining is not a mere neutral force, but a personal act issuing from Trinitarian communion. Teleostability therefore takes on a deeply relational dimension: each being exists because it is willed, known, and upheld by a Person. Man, created in the image of God, is called to enter consciously into this relationship and to reflect it in his relationship with the world.

This is why teleostability opens onto a metaphysical ecology. Respecting life is not merely an ethical or ecological imperative: it is to recognize and honor the vital bond uniting every creature to its Creator. To destroy, waste, or exploit without measure is to break that bond and to oppose, at our own scale, the order willed and upheld by God. Conversely, to protect, restore, and beautify creation is to cooperate in the divine work, to participate in this great dynamic oriented toward the telos.

Ultimately, teleostability reminds us that we do not live in a universe abandoned to itself, but in a cosmos constantly visited by the Presence. It invites us to see in every being — from stars to flowers, from animals to human faces — a sign of this continual action. This is the very proof that God is Person and Love: a mere “god of the philosophers,” reduced to an abstract essence, would absorb or crush all reality into itself. The true God, on the contrary, is the One who gives Himself without being confused, who sustains without overwhelming, who causes all to be while allowing each being to exist. It is an invitation to live not as masters or predators, but as active participants in the harmony that God upholds and leads to its fullness.

Comments